The 50th anniversary issue of Criminal Justice and Behavior Vol. 52, Issue 3, March 2025) has published a new study by Julie Blais, R. Karl Hanson, and Andrew J.R. Harris that revisits a 2000 case-control study of risk factors for sexual recidivism (Hanson & Harris), also originally published in CJB. By examining updated information on the original sample subjects collected in 2017, the researchers were able to further compare those who re-offended and those who did not by differentiating the risk factors observed in the original case-control study and those in the new prospective cohort model. While most of the comparisons favored the prospective cohort study design, the researchers ultimately determined that the differences were not significant, with both static and dynamic risk factors approximately equivalent. This led them to conclude that the case-control study model remained viable when identifying risk factors for behaviors such as sexual recidivism.

Background

Study Models

“Prospective studies are still considered the gold standard because the temporal order between risk factors and the outcome of interest is easily established. But to what extent are the findings between the two research designs equivalent?”

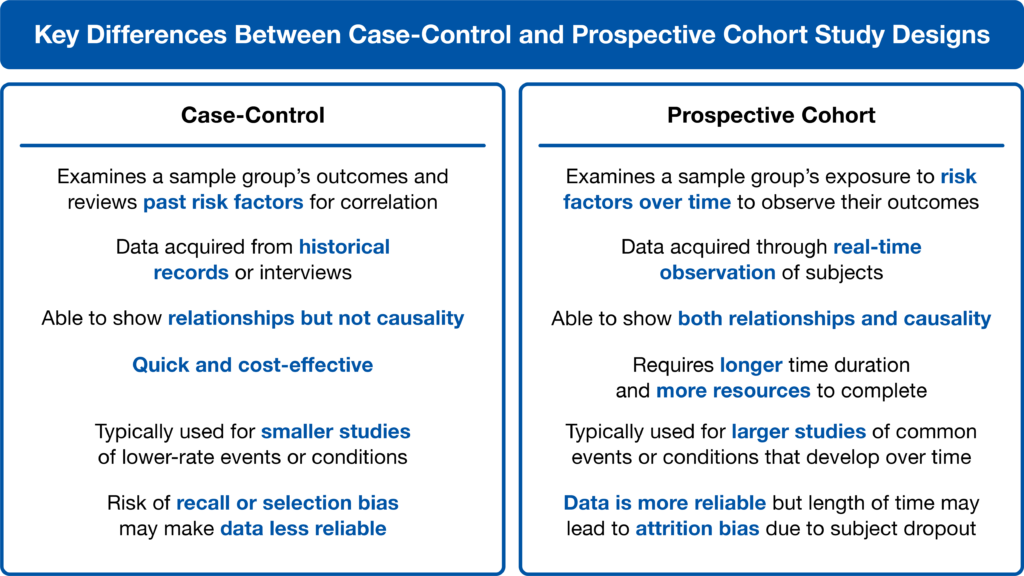

Case-control studies were designed to be a short and cost-effective method of observational research on events that have relatively low occurrences. They begin by collecting samples of cases (in which the event occurs) and of controls (in which it does not) and then comparing them through a retrospective lens to determine risk factors. These studies rely on historical records such as medical files, interviews, or previous assessments, and are subject to limitations that include recall bias and the fact that while relationships between risk factors and outcomes can be established, causality cannot.

In contrast, the prospective cohort study employs a forward-looking design that follows a sample group over time to see how the risk factors affect outcomes. This allows the study to better identify how risk factors may contribute to the event in question. This model is typically used for much larger research projects in public health sectors, such as an examination of chronic conditions or a more general review of criminal reoffending. While requiring more resources, the data is often considered more reliable.

The goal for this study was to follow up on the data from the 2000 case-control study of sexual recidivism among justice-involved men in Canada and determine whether those initial findings were consistent with the more robust data offered by the 2017 prospective cohort study. To the researchers’ knowledge, this model of following a case-control study with a prospective cohort study on the same sample of sexual recidivism subjects is the only one ever conducted in this manner.

Risk Factors for Sexual Recidivism

Research into sexual recidivism has determined two primary categories of risk: factors that are specific to sexual offense and more general antisocial behavior traits. Characteristics in the sexual offense dimension include:

- Early onset of sexual offense behaviors

- Commission of diverse forms of sexual offense

- Atypical sexual predilections, such as behaviors connected to pedophilia

- Sexual preoccupation

General antisocial traits include:

- Propensity for rule-breaking

- Issues with adjustment during childhood

- Poor impulse control

- Lack of problem-solving skills

- Callousness or other antisocial personality traits

- Difficulty in maintaining healthy relationships

In the 2000 case-control study, a sample size of over 400 male sexual offenders was examined for both static and dynamic risk factors. Cases were matched across demographic characteristics as well as factors specific to sexual crimes, including ages of the offender and victim, and criminal history. Sexual recidivism risk levels were also determined using the Rapid Risk Assessment for Sex Offense Recidivism (RRASOR) tool. The 2000 study found that the risk factors most likely to indicate recidivism were:

- High incidence of violent behavior

- Sexual deviance (paraphilias and types of victims)

- History of childhood sexual abuse or neglect

- Antisocial attitudes

- Poor social influences

- Feelings of sexual entitlement

However, this study design may have led to inflated effect sizes for more general risk factors and reduced sizes for other variables, and variables such as RRASOR scores could not be meaningfully tested. As a result, it was uncertain that these risk factors would be replicated in the prospective cohort study.

Methodology

Research Subjects in Case-Control Study

The 409 men examined in the 2000 study had been convicted of sexual assault of a physical nature against a victim who was not within their immediate family – in other words, cases of familial abuse or noncontact sexual offenses were excluded. All offenders had all served a segment of their sentence under community supervision between 1992 and 1997. Cases were selected from across all Canadian provinces except Prince Edward Island, with 208 classified as sexual recidivists and 201 classified as non-recidivist up to the point of the 1997 data collection. The researchers matched recidivist and non-recidivist cases across characteristics such as:

- Ethnicity

- Location

- Jurisdiction (federal or provincial)

- Occurrence of major mental illness

- RRASOR scores

The case-control study indexed several recidivism events ranging from exhibitionism to actions indicating that sexual offense was imminent, such as making an approach on victims. These were categorized as:

- Sexual offense charges (68%)

- Violations of supervision for sexually motivated behavior (26%)

- Nonsexual charges with sexual motivations (6%)

Research Subjects in Prospective Cohort Study

The updated criminal history of these 409 men gathered for the 2017 prospective cohort study led to reassessment and reclassification of some cases in the original data – for example, 27 cases originally labeled as recidivism were shown to have either received new charges outside of the frame of the supervision period or to have been mistakenly deemed a sexual offense. The result of the reassessment saw a sample of 407 men that included 180 recidivists and 227 non-recidivists.

The prospective cohort study reviewed only the 227 men who should have been classified as nonrecidivists in 1997. All had successfully completed an average of 24 months of community supervision at the time of data collection, and subsequent criminal history information identified 57 of these 227 men as having committed a new sexual offense, with information unavailable for 14 other cases. The prospective study’s new sample therefore compared 57 men who were known to have committed a sexual offense after their assessment date in 1997 to 156 men who had not reoffended prior to the follow-up end date in 2017.

This new cohort expressed the following demographic characteristics:

- Average age at time of release: 39.4 years old

- Median education level: 10th Grade

- Racial/ethnic background

- White: 85.0%

- Indigenous: 8.8%

- Black: 2.9%

- Unknown/Other: 3.3%

The cohort was also assessed for risk of sexual recidivism using the Static-99R tool, which showed a higher-than-average risk within the group:

- Very low risk: 1%

- Below average risk: 4.9%

- Average risk: 28.7%

- Above average risk: 30.7%

- Well above average risk: 34.6%

Key Findings and Interpretations

The researchers made comparisons between the results of 82 distinct static and dynamic risk factors in both the 2000 case-control and 2017 prospective cohort studies. These 82 factors were further classified as such:

- Sex-crime-specific factor (28)

- General crime risk factor (34)

- Other (20)

Within the 28 sex-crime-specific variables, 14 variables showed larger effects in the case-control study while the other 14 variables showed larger effects in the prospective cohort study. Only seven of these were deemed statistically significant, with four favoring case-control and the other three favoring prospective cohort design.

Within the 34 general crime factors, 21 variables in the prospective cohort study showed larger effects compared to only 13 in the case-control study, but only 11 of these differences were statistically significant with 7 that favored prospective cohort design and 4 favoring case-control.

The research team had initially predicted that sex-crime specific variables would show larger effects within the prospective cohort study design; in fact, the pattern that emerged was the exact opposite.

Broader studies of sexual recidivism risk are also referenced by the research team in their discussion of the findings. For example, both the 2000 and 2017 study designs indicated a significant positive correlation between subjects experiencing childhood sexual abuse and later sexually recidivist behavior. While prior studies have shown that men who commit sexual offenses had also shown high rates of experiencing this abuse, no prior prospective studies had shown that recidivism was also associated consistently. They also observed that certain tools used to predict sexual recidivism (such as Static-99R) may need to be re-examined in light of their findings. For example, sexual offenders who targeted younger male victims showed high risk of recidivism, but the opposite effects were seen when the victims were adult males. On tools that score for “male victim” more broadly, the data being collected may need greater differentiation.

Conclusions

The results of the study support these conclusions:

- Case–control and prospective cohort designs can provide similar information on risk factors for sexual recidivism

- Matching on specific factors in case–control studies can have unexpected effects on the observed relationships

- The factors identified through both designs are largely consistent with the broader literature on sexual recidivism risk

“A primary concern with the use of case–control studies is that the ease with which they can be implemented may lead to a lack of rigor compared to how they should be conducted.”

The study maintains that while prospective cohort studies are an overall more effective research model, case-control studies remain viable and valid when the outcomes being tested have a lower base rate (such as sexual recidivism). The researchers note that there are nuances to be considered within their findings, such as the understanding that while case-control studies may continue to offer useful data, the implementation of any such study will affect the overall quality of the data. To that end, they suggest several recommendations for case-control study design:

- Build equivalency between compared case and control groups by matching population, location, and setting of individuals experiencing the outcome (such as sexual recidivism).

- Institute individual-level matching variables on the study’s cases for factors such as age or sex that could influence the results but have no substantive connection to the research questions.

- When possible, engage multiple sources of information – in studies that rely on interviews, for example, additional high-quality sources can counteract recall bias that are common in this study design.

- Ensure that measurable risk factors were present prior to the outcome being studied.

The authors do nonetheless caution against a perspective that assumes a prospective cohort study is inherently superior to a case-control study. Several limitations are common across both models, including those caused by matching and other preselection biases. Furthermore, there are always random errors to be found in data sets that cannot be handled simply through the choice of study design.

Source Article: https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/full/10.1177/00938548241291155