A new study of correctional rehabilitation programs conducted by Susan Dewey, Brittany VandeBerg, and Susan Roberts–published in Vol. 104 (2) of The Prison Journal earlier this year–provides a distillation of three methods for delivering those services: holistic, pragmatic, and community oriented. Based on observations and interviews with hundreds of non-uniform correctional professionals working in eight different prison systems in the United States, the researchers manage to draw detailed outlines of each strategy, as well as identify both the strengths and weaknesses of each.

Background and Research Purposes

Non-uniformed staff fulfill several different roles outside of the responsibilities of correctional officers, each of which contribute to the routines and social climate of a correctional facility. These roles include:

- Administrators

- Mental health counselors

- Teachers

- Group facilitators

- Vocational instructors

The various activities they oversee–which include education, reentry preparedness, and family-connection work–help cultivate a prison environment conducive to rehabilitation that subsequently reduces the risk of recidivism when incarcerated individuals complete their sentences. By engaging with prior academic literature and gathering perspectives from these personnel, the researchers sought to understand the frameworks that constituted a successful rehabilitation program, as well as the obstacles that each framework might face in their particular facilities.

“Positive prison social climate is inherently therapeutic in orientation because it requires supportive communication and the belief that incarcerated people can change their lives for the better and avoid recidivism post-release (Bennett & Shuker, 2018).”

Methodology

To conduct their study, the researchers contacted the administrators of 12 state prisons from different American geographical regions, looking to gather a diverse array of experiences. Eight of those prisons agreed to participate in the study, and for purposes of specific anonymity, the researchers characterized them by region as follows:

- Appalachia

- Deep South

- Great Lakes

- Great Plains

- Midwest

- North-Central

- Urban East Coast

- West

These eight prisons represented not only different regions, with particular cultural differences in the surrounding communities, but also different facility sizes.

To collect the data needed for the study, lead researcher Susan Dewey spent an average of ten days at each prison. Each visit included interviews with correctional staff responsible for overseeing rehabilitation services, as well as separate interviews and observation of rehabilitation participants. The interview questions themselves were designed by Dewey and researcher Susan Roberts, prompting responses on five larger themes:

- Successes (questions regarding program achievements)

- Instruction (questions regarding educational delivery methods and processes)

- Student profiles (questions regarding the backgrounds of prisoners within the program)

- Student motivation (questions regarding incentives to succeed in the program and impacts of individual characteristics for each student)

- Collaboration (questions regarding relationships with other agencies)

On average, Dewey interviewed 30-50 staff members at each prison, with 5-15 of these staff members being senior staff. Conversations ranged from short, informative interactions to phone calls that lasted multiple hours at a time.

Findings and Interpretations

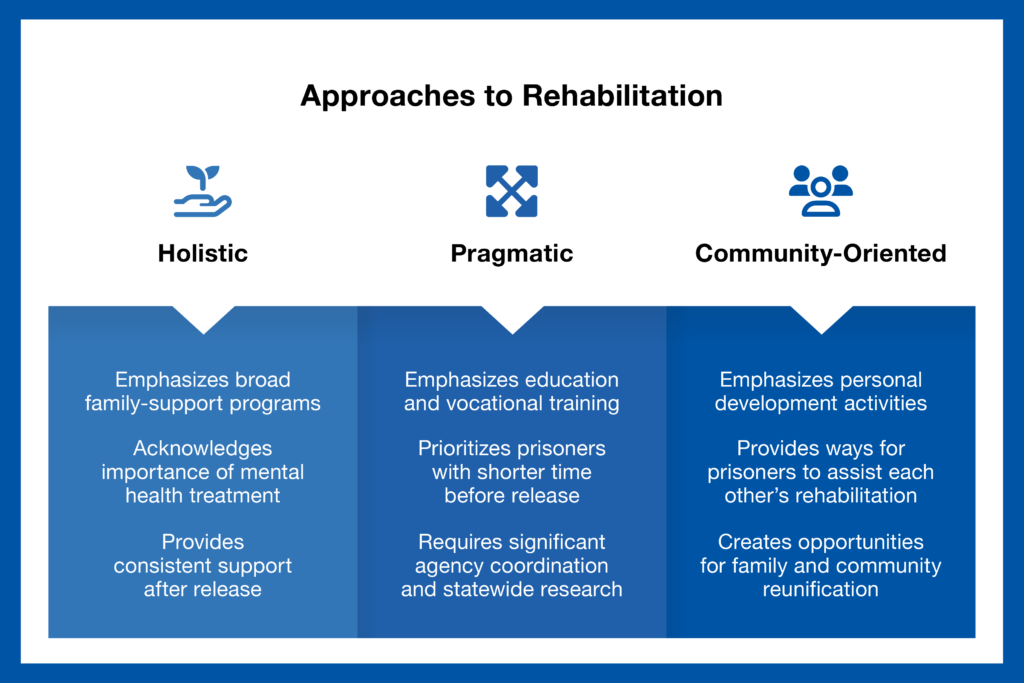

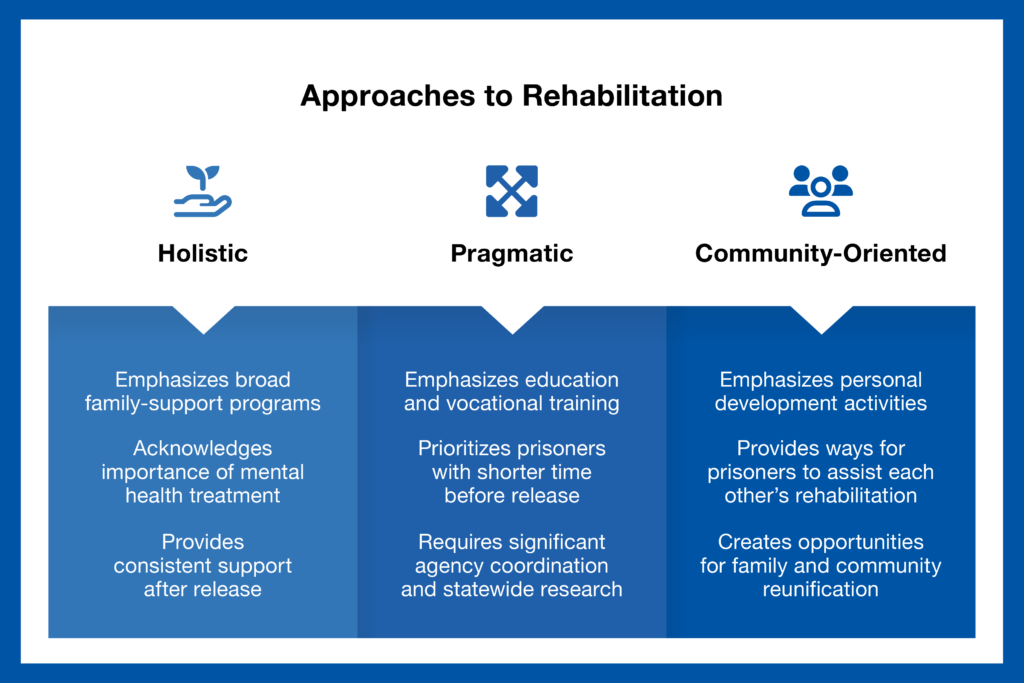

Based upon these hundreds of interviews, the researchers identified three distinct approaches towards providing rehabilitative services in prison.

The Holistic Approach:

This approach “serves all incarcerated people, irrespective of sentence length, and argues that rehabilitative services should encompass the totality of an incarcerated person’s needs through team-based efforts by security, mental health, education, and case management staff.” Family support services and mental health treatment are emphasized within this system as a means of reducing the likelihood of recidivism. One well-known example of this approach is the Norwegian “import model,” which also establishes consistent support for prisoners after their sentence is complete, with educators, healthcare providers, and other non-uniform staff continuing to offer services after release.

However, critics of this approach point out that there are complicated hurdles to employing a fully holistic model, including:

- Restrictions on time and/or space for classes or group meetings

- Security concerns and emergency lockdown protocols

- Facility transfers

- Expected limitations on contact between staff and former prisoners

Others also note that the inherent power dynamics in correctional facilities run counter to the supportive environment a holistic approach seeks to create.

Despite these concerns, the researchers did hear from their study participants that they considered two aspects of a holistic model to be effective: (1) the use of individual assessments and evidence-based programs built from the assessment data, and (2) greater focus on mental health or substance abuse disorders that required diagnosis and treatment. Administrators and other staff from the Midwestern and North Central locations described how assessments were used to build better case plans and ensure that prisoners were being directed to the correct rehabilitation programs for their needs. Multiple administrators across the study sites also described the importance of looking past an inmate’s criminal history at the possibility that they suffered from a mental health disorder in need of proper medication.

Both strategies also relied on well-implemented procedures for inter-staff communication–such as mandatory weekly meetings to keep all personnel informed–and clear distinctions between uniformed or non-uniformed staff. A participant from the Appalachian research site described the roles succinctly: “uniform staff [are] solely responsible for maintaining safety and security and non-uniform staff [are] responsible for therapeutic programs and classes.” This clarity not only prevented non-uniformed workers from being asked to handle unsafe situations they were not trained for, but also engendered trust within the prisoners that the rehabilitation program was being administered by appropriate professionals.

Regardless of the methods employed in each prison, study participants agreed that a successful holistic approach required a well-articulated mission with a philosophy and implementation understood and practiced by all staff.

“A Great Plains participant noted the importance of training all staff in core correctional practices to bolster awareness of criminogenic factors and provide staff with the tools ‘[to] address behavior by starting with the least restrictive discipline, using communication skills, using reflective listening.’”

The Pragmatic Approach:

This approach is underpinned by the idea that “rehabilitative services should result in increased work opportunities by tailoring vocational training to statewide needs among employers willing to hire formerly incarcerated people, engaging in multi-agency coordination to provide realistic workforce training, and forming partnerships with agencies to ease the transition to community.” Programs are built around high school equivalency and vocational training in addition to mental health services, and are prioritized towards those prisoners with shorter-term sentences. The explicit aim of this rehabilitative approach is to provide both the skill sets and opportunities to attain and keep employment after release, which studies have shown to be a key factor in reducing recidivism.

There are, however, systemic barriers to former prisoners finding employment, and those who are opposed to the pragmatic rehabilitation approach argue that a focus on training prisoners to be productive workers–rather than placing an emphasis on how education can help empower and improve an individual–is dehumanizing.

The researchers determined that a successful pragmatic approach required three key facets:

- Understanding of statewide employment needs and employers willing to hire former prisoners

- Multi-agency coordination to establish relevant training programs around these needs Agency partnerships that provide transitional support back into communities

Research of a region’s most pressing workforce needs give the correctional system a roadmap for their rehabilitation efforts. This research also requires state agencies to confirm that employment opportunities within that workforce exist among businesses willing to hire a formerly incarcerated individual. A participant in the Western location discussed a three-year cycle of surveying local employers; in one instance they learned that home construction was experiencing a labor shortage, while in another instance they learned that auto body and painting work was a viable post-incarceration career path. Vocational programs in the facility were adjusted accordingly. Job fairs also play a vital part in making this facet functional.

The establishment of relevant training programs requires a “realistic” view of employment opportunities for former prisoners. A participant from the North Central location gave examples of forklift management and recycling certification as feasible, and administrations from the Midwestern, Western, and Great Plains facilities offered a carefully screened option for some prisoners to work off-site with prospective future employers, while drawing a salary that can be used to pay off punitive fines or send money home to their families.

By coordinating with agencies dedicated to post-incarceration transition, the programs are also able to assist by providing required documentation or preparing a resumé. Non-profit organizations may also be partners with a correctional facility to inform prisoners about community services that will be available to them both before and after their release. In the Deep South and North Central administrations, for example, resources are provided for:- Skills-based training

- Assistance for military veterans’ benefits

- STD testing

- SNAP program assistance

- Child support payment assistance

By assuring that formerly incarcerated individuals are able to return to their communities on solid footing, the pragmatic rehabilitation approach aims to reduce the likelihood of recidivism.

The Community-Oriented Approach:

This approach advocates that rehabilitative services should be reframed as “positive social change by providing incarcerated people with opportunities to model good citizenship both in prison and in community, including through peer mentoring.” In other words, rehabilitation consists of encouraging a prisoner’s view of themselves as a member of society who can make positive contributions, allowing them to reunite with both their families and communities. This approach also, uniquely, frames the correctional system as an institution that has been historically weighted against marginalized individuals due to systemic racism, classism, and condescension towards those with substance abuse issues; as such, it makes a point to serve all prisoners regardless of crime or sentence.

This approach may be considered “idealistic,” however, and critiques of community-oriented rehabilitation point out that correctional facilities are mandated to first be secure. There is also a seeming contradiction within this approach, in that prison must be understood as an institution that “punishes, rehabilitates, oppresses, and protects public safety” all at once.

Study participants identified multiple opportunities to model better citizenship both within the facility and after release, including:

- Cohabitation between prisoners with shared personal development goals

- Incentive-based models of acknowledging success

- Peer support and leading facilitation groups within the prison

- Reconnection with family members

- Work that creates positive community impact

- Interactions with community leaders

- Providing peer support for other released prisoners

The advantages of a shared housing setup were mentioned by participants from several regions, with one response from Appalachia adding that there were particular benefits to housing prisoners with similar goals and circumstances who were within a year of completing their sentences, as “this short timeframe enabled provision of a specialized curriculum which, in turn, dramatically improved interactions between incarcerated people and staff.” They did note, however, that the relative safety of such living arrangements in comparison to the general population presented a double edge–the prisoners had motivation to make progress in their program to feel more secure, but a participant in the Urban East Coast location observed prisoners deliberately failing high school equivalency exams to remain in their education unit.

As prisoners showed progress in their rehabilitation, incentives offered included tangible rewards such as student-of-the-month distinctions and special meals, as well as new opportunities for greater responsibility and activity. In the Urban East Coast and Appalachian facilities, for example, prisoners were allowed to set up their own facilitation groups and even submit program proposals for review. In the Deep South location, prisoners started facilitation groups and also engaged with their community by supporting social clubs among their fellow incarcerated individuals.

Peer tutors and mentors volunteered to assist paid teaching staff, often by using their common experiences to better relate to students. In the Western location, these peer tutors were acknowledged for “making academic material relatable to incarcerated people who may not have had positive experiences with education prior to their incarceration.” Some participants did note the need for peer mentor training, however, as the nature of the correctional environment does not tend to provide positive models for one prisoner having authority over another.

Reunification with family and opportunities to assist the outside community are crucial for the success of a community-oriented approach. Some facilities provide multidimensional options to encourage family connections, such as cooking courses, letter-writing programs, family days, and graduation ceremonies. Some also devised novel ways to give prisoners responsibility over initiatives that benefited the outside community, such as fundraisers for domestic violence victims or growing fresh produce to be donated to food depositories.

Finally, this approach attempts to create openings for former prisoners to come speak or lead groups for those involved in the rehabilitation process. This form of peer support offers benefits to both the incarcerated individuals and those who have been released.

Graduation events hosted by the Appalachian administration have featured governors, attorney generals, and other well-known people to celebrate incarcerated people’s success along with their invited guests, with guest lists sometimes including over three hundred people.

Conclusions

The research team acknowledges that there are very few comparative studies available that illustrate best practices for non-uniformed correctional staff to facilitate rehabilitation. The three approaches that the study identified–holistic, pragmatic, and community-oriented–each offered their own particular advantages as they were implemented across different regional correctional institutions. The participants did also describe common challenges to all approaches:

- Larger prison populations cause delays in implementation

- Untreated or undiagnosed mental health conditions were obstacles to program goals

- Scarcity for continuity of care, external partnerships, and other resources outside of the facility

The study participants did largely express enthusiasm for their programs, and believed there was value in continuing to develop and share innovative approaches in rehabilitation.

Source: Approaches to Successfully Delivering Rehabilitative Services in Prison: Perspectives from Non-Uniform Correctional Staff in Eight States (The Prison Journal 2024, Vol. 104(2)), Susan Dewey, Brittany VandeBerg, and Susan Roberts